Examples

Magnetically confined surface excitons in a layered antiferromagnet

Excitons in molecular and two-dimensional (2D) systems have long been known, a unique capability emerges when the system is magnetic and possesses tightly bound excitons with large oscillator strengths, because they are tunable with magnetic fields, and provide a rich playground for interesting and novel technological applications. In a recent collaboration with the Basov group at Columbia University, excitons in the van der Waals 2D magnet CrSBr were observed and the optics modeled with the Quasiparticle Self-Consistent GW + BSE approximation. This study elucidates in detail the evolution of excitons observed with layer thickness. Optical spectroscopy (reflectance and photoluminescence) when combined with many-body perturbation theory, demonstrates that some excitons are confined to surface layers and others are like conventional, bulk excitons.

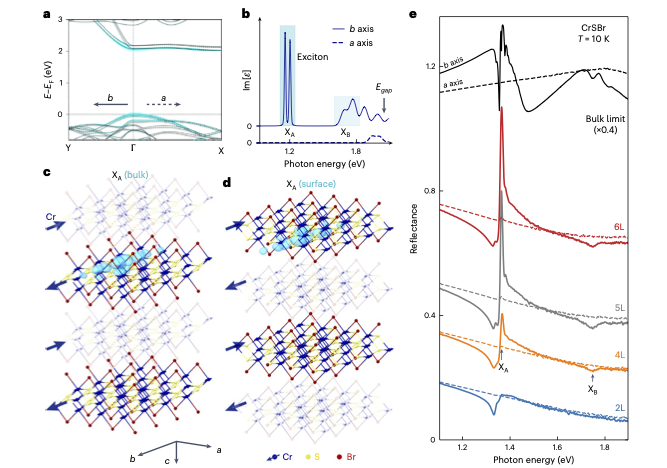

Magnetic surface excitons exhibit stronger Coulomb attraction, leading to a higher binding energy than excitons in bulk layers, and profoundly alter the optical response of few-layer crystals. Distinct magnetic confinement of surface and bulk excitons is established by layer- and temperature-dependent exciton reflection spectroscopy, and and are corroborated in detail from many-body perturbation theory calculations within Questaal. The latter captures the observed evolution with layer thickness, and is at the same time can characterize their spatial structure in detail (See Fig. 1 c,d), as well as the energy bands from which the excitons originate (Fig. 1 a).

Binding of electron–hole pairs, called excitons, tend to be strong in 2D systems compared to their bulk counterparts, because the screening of the coulomb interaction (which plays a central role in determining the electron binding energy) is less effective there. Binding energies of 0.5 eV and higher are often observed. Multilayered materials whose layers are bound by weak van der Waals interactions are similar to the 2D (i.e. monolayer) counterparts; however interlayer interactions modify the band structure of the isolated monolayer, making the excitonic properties highly sensitive to layer thickness.

In MoS2, for example, the photoluminescence (PL) of the monolayer is dramatically larger than the bilayer, in large part because the monolayer is direct-gap while the bilayer has an indirect gap.

CrSBr is somewhat different. Monolayer CrSBr is highly anisotropic in the plane, as seen in the the sharp difference in energy bands along the a-axis (the T-Γ line in Fig. 1 a) and the b-axis (the Γ-X line). The large anisotropy causes excitons to exhibit large oscillator strengths. The lowest-energy (A) exciton wave-function is similarly highly anisotropic. Its pencil-like shape extends over many neighbors along the b-axis, but is extremely confined along the a- and c- axes. The band structure, dielectric function, and exciton wave-function are all strongly anisotropic in CrSBr. Furthermore, it is magnetic: At low temperature Cr spins are aligned ferromagnetically in plane, layers are antiferromagnetically coupled. Above the Néel temperature at TN = 132 K, it becomes paramagnetic where the spins are no longer ordered. This change has important consequences for the excitons, as described below.

The local Cr moments are responsible for the gap opening. As QSGW typically overestimates the bandgap in transition metal insulators, W has to be enhanced with ladder diagrams (W → Ŵ) to obtain a high-fidelity band structure.

Evolution of excitons with layer thickness and temperature

By comparing layer-dependent exciton absorption, PL with ab initio ab initio BSE calculations, the quantum-confined nature of both surface and bulk excitons in CrSBr can be established. Both yield essentially the same result, which gives high confidence in the interpretation of the experiment.

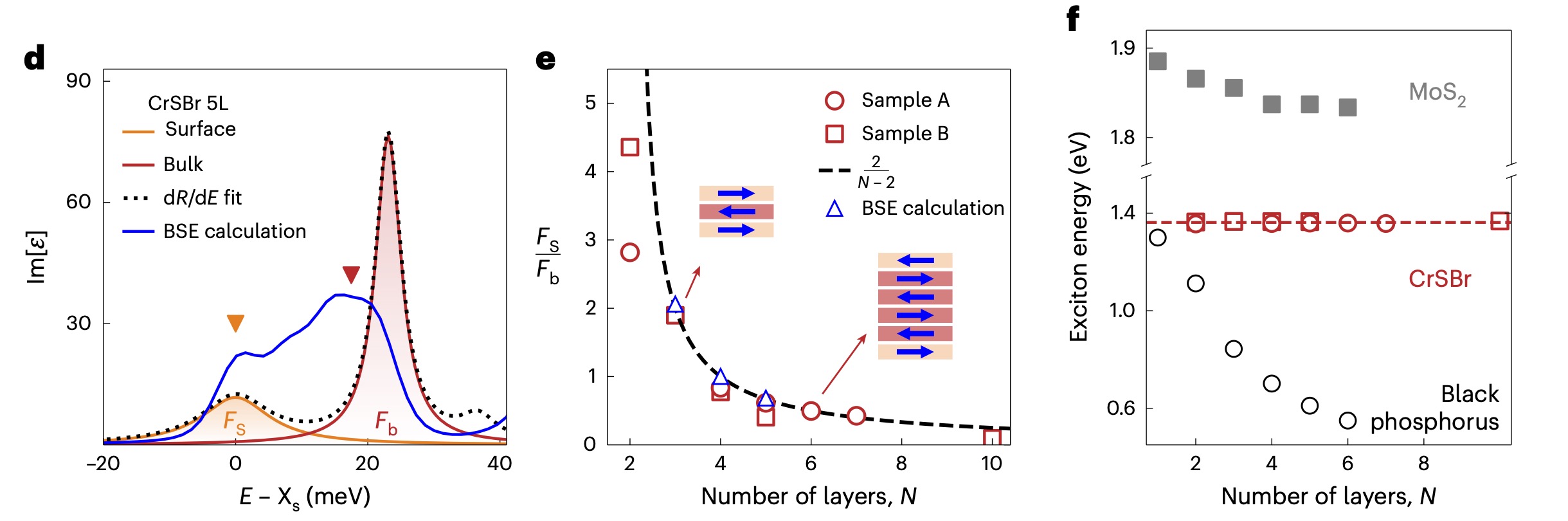

First, two peaks of the XA exciton can be distinguished, separated by ~20 meV (Fig 2d), observed in both BSE calculations and in reflectivity measurements. Theory can also elucidate their wave function character (Fig 1c,d), showing that the slightly more bound exciton is confined to the surface, and the less bound confined to the bulk. The increased binding of the surface exciton can be understood as a reduction of screening at the surface, thus increasing the electron-hole attraction and the binding.

Second, the ratio of peak intensities Fs and Fb of the two excitons approximately follows a simple expression, 2/(N−2); see Fig 2e. (Theoretically the oscillator strengths given as a direct byproduct of the theory; experimentally it is inferred from the area under the curve.) which is what is expected when excitons in each layer are completely decoupled.

Third, exciton binding is independent of layer thickness from the monolayer to the bulk limit, both theoretically and experimentally (Fig 2f). This stands in sharp contrast to MoS2 and black phosphorus.

That binding energies and oscillator strengths are conserved in each layer is very important from a technological perspective, as it enables CrSBr to be highly scalable.

Finally, the temperature dependence of the exciton binding and linewidth was studied experimentally. It was not calculated from ab initio theory. A theoretical study of bulk CrSBr of the one-particle spectrum shows a difference above and below TN, aligning very closely with ARPES measurements in both cases (see also this summary). The most important take-away from the optical measurements is that the excitons show a markedly different temperature dependence above and below TN. This is interpreted as a reduction in the confinement of the surface exciton with increasing magnetic disorder.

PAPERS · EXCITONS · 2D MAGNETS